The Pomors had oceangoing vessels called kotch that could carry them across the Barents Sea to Svalbard. Pomor kotch off the Chukchi Peninsula. 1647. (Aquarelle: Gordon Miller)

The Pomors had oceangoing vessels called kotch that could carry them across the Barents Sea to Svalbard. Pomor kotch off the Chukchi Peninsula. 1647. (Aquarelle: Gordon Miller)

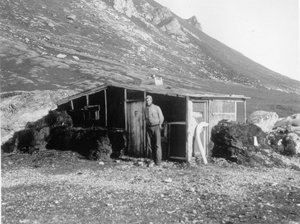

Wilhelm Matheson outside the cabin at Gnålodden on 28 August 1936. (Image: Anders K. Orvin / The Norwegian Polar Institute)

Wilhelm Matheson outside the cabin at Gnålodden on 28 August 1936. (Image: Anders K. Orvin / The Norwegian Polar Institute)

Russian site. Remains after a hunting station on the west coast od Spitsbergen. (Image: Kristin Prestvold / The Governor of Svalbard)

Russian site. Remains after a hunting station on the west coast od Spitsbergen. (Image: Kristin Prestvold / The Governor of Svalbard)

The mighty, tall and beautiful Hornsundtind is usually the first mountain you see when you approach Spitsbergen from the south, at least if you arrive by boat. In good weather and with fair visibility the mountain can be spotted at a distance of 75 to 85 nautical miles. When Jonas Poole reached Spitsbergen in 1610 onboard the ship Amitie, Hornsundtind was the first mountain he spotted. He called it Muscovy Companies Mount after the English trading company he sailed for. A bit further north he discovered the entrance to Hornsund, and called the southern shore of the fjord mouth Lord Suffolk Point. Poole sent a boat ashore to explore the coast more closely. When the boat and crew returned they brought a reindeer antler, which resulted in the name Hornsund (Antler Sound). Poole attempted to enter the fjord with the ship, but was hindered by strong off-shore winds. There was also plenty of drift ice and it was not possible to find a good harbour. Later the fjord was called Hoorn baye, Horensont and Oresont.

In the summers following 1610, ships repeatedly visited Hornsund. At first they mapped the area and explored the coastline and the resources in the fjord. Later ships came for trial whaling, and after a few years whaling became more permanently based in Hornsund. The skills of whaling were slowly acquired through testing and failure. At the beginning of the 17th century, only the Basques had whaling skills, acquired through decades of whaling in the Bay of Biscay and at the Labrador coast. The crew onboard the vessels heading north at the start of the 17th century normally included some Basques, so that the other members of the crew could learn the skills.

In 1614, an agreement between the Dutch and the English on the rights to the different whaling grounds in Svalbard granted the English control of Hornsund. The English built several whaling stations on the southern shore of Hornsund, in Gåshamna and at Höferpynten. Despite the agreement, the area was subject to several conflicts in the following years, including a conflict with the Dutch whalers in 1617. Hostility was obvious between the two groups, but no fighting occurred. After protracted negotiations that summer the area was re-established as English territory. From 1624 and onwards Hornsund was one of the main strongholds for the English whaling fleet, and the remains of their stations can still be seen, best visible in Gåshamna.

Hornsund has always been rich in hunting resources such as Arctic fox and polar bear. As a result of the prevailing currents drift ice is pushed into the fjord early in the season, and the fjord’s ice cover is therefore often formed relatively early in the autumn. The ice conditions attract polar bears that hunt on the ice. For these reasons Hornsund was also an attractive area to the Pomors in the beginning of the 18th century. The Pomors were Russian overwintering trappers who concentrated on walrus products – ivory, blubber oil and hides – and furs from polar bear and Arctic fox and down. They also hunted reindeer, seals, birds and collected eggs. The Russian hunters preferentially settled along the south side of Hornsund and the low strand flats south of the fjord entrance during their overwintering expeditions in the 18th and 19th centuries.

There was year-round activity at most of the Russian trapping stations. Some of the stations were large and the remains today consist of sites of buildings that must have had many different functions. The sites are easily recognized by the cogged joint construction technique and the vertical-post log construction technique in which horizontal planks were slotted between two bearing posts. Also characteristic is the location of the open fireplace, built in red brick on a sturdy platform. Inside and around the remains of the buildings you often find artefacts giving clues to life at the time – game pieces, kitchen utensils, trapping contraptions, boat equipment, iron and wooden artefacts, ceramics, textiles and pieces of leather. The trappers made different crafts to work up the raw materials into valuable commodities; this pastime occupied them during the long polar night when wind and cold kept them indoors.

Around the trapping stations are rubbish heaps with bones from birds, fish and other animals, which fertilize the ground and give the area a green and lush vegetation. Cultural remains in Svalbard can often be identified through the lush vegetation overgrowing the sites.

Foundations for Russian Orthodox crosses are in the vicinity of several of the Russian trapping stations. The large wooden crosses once erected by the Pomors could have served different purposes, including protection, bringing luck in hunting and/or as grave markers and territorial markers. The crosses also functioned as navigational signs.

The Norwegian overwintering trapping in Hornsund started in the early 20th century, and was largely based on the same products as the Pomor trapping. The goal was always to hunt as much to earn a good profit. The trappers had to endure isolation, loneliness and tiny living quarters, and they had to survive all the imminent dangers and stand the cold polar night. The trapping territories were organized with one main station and – usually at a walking distance of one or more days from each other – several satellite stations (cabins) within the hunting grounds. Fox traps were placed at fixed intervals in the fox areas, and self-firing gun traps were placed in the polar bear areas. In her book from 1956, the Norwegian trapper Wanny Woldstad describes the gun traps as follows:

“A self-firing gun trap is usually a Remington rifle with half the barrel cut off. It can be a rifle or a shotgun of any calibre, the higher the better. It is mounted in a reasonably sized box with a delicate bait of blubber attached to a string, which again is attached to the trigger at the other end. This is an effective and quick-acting weapon”.

The self-firing gun trap was invented in Svalbard for local use. It was more efficient than the polar bear population could withstand, and the population was severely diminished. Some areas were used for both fox and polar bear trapping, and both species were trapped in the wintertime when the fur is at its best.

One example of a trapping territory with a main station and satellite stations is the main station in Hyttevika – north of the entrance of Hornsund – and its satellite stations in Isbjørnhamna and Gnålodden. The distance from Hyttevika to Isbjørnhamna is about 11 km , and it is another 8 km to Gnålodden. Along these legs fox-traps and self-firing gun traps were distributed and had to be tended at regular intervals. It is a difficult landscape to walk, with large glacier fronts terminating at sea, steep slopes falling into the sea, rocks or screes. The trappers had to overcome all of these hazards and challenges in their work.

The mining company The Northern Exploration Company Ltd., from London, undertook explorations of the southern part of Hornsund from the beginning of the 20th century without luck. The trappers sometimes served as watchmen for the NEC.